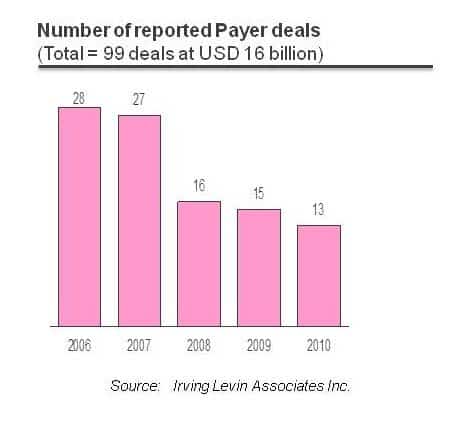

Before the economic crisis began in 2008, some ambitious forecasts predicted that by now due to industry consolidation less than 50 large health plans would comprise the entire market. Economies of scale were so attractive in the health insurance industry that even such an aggressive consolidation scenario didn’t sound unrealistic. Obviously, it didn’t happen.

The question is, why? Was there some type of intervention that disrupted the natural evolution path of the health insurance industry and prevented the “presumably inevitable” consolidation, just as human intervention kept the Leaning Tower of Pisa from toppling? Before we address that question, let’s briefly talk about the fundamental premises for consolidation.

There are multiple benefits to being a big player in the U.S. health insurance industry. First, you gain access to the most lucrative client segment in this industry, the Fortune 1000 companies, as it procures health coverage for its employees in a single national chunk, rather than location by location. The Fortune 1000 target category is also the most attractive client segment because of the fixed cost associated with each sales pursuit, which can be spread across a much higher number of beneficiaries, as opposed to closing a deal with a “Mom & Pop” shop. Obviously, to be able to serve such mega clients on the national level, medium-sized firms were expected to close the gaps in their geographic footprint, and selectively acquire niche/state level players.

Second, locking down a large number of beneficiaries allows health insurance companies to exert pricing pressure on providers of medical services, while simultaneously withstanding pricing pressures from more consolidated adjacent healthcare verticals such as pharma and medical device manufacturers. Essentially, large insurance firms are discouraging their customers from consuming out-of-network services, while demanding from in-network providers extremely favorable pricing, frequently in the form of low-priced, fixed monthly payments independent of the actual volume of patients (“capitated contracts”).

Third, due to the very high level of regulation on the federal, state and local levels, as well as quite complicated value chain processes, for every industry player there is an almost mandatory cost category associated with various compliance measures, proactive legal support, and lobbying. Obviously, the bigger you are the more you can afford to spend in this direction (or the less this expense item contributes to your overall cost structure percentage-wise). This is especially true for those firms that deal with Medicare and Medicaid programs, where reimbursement requirements are changing almost on a monthly basis, and staying compliant requires an enormous effort.

With these strong driving forces, why did the expected consolidation trend de-accelerate? Several credible sources point to the recent financial crisis as a primary inhibitor, but I personally don’t think it played any major role in this situation.

I think we should mainly look at President Obama’s healthcare reform. It impacted the operating model of the industry in many ways – the medical loss ratio (MLR) requirement, preexisting conditions, individual buyers, and new coverage limits, to name just a few. Basically, healthcare reform brought so many changes to the fundamental operating principles of the industry that adapting to them requires a significant change management effort. Moreover, as reform impacts not only health insurance but also the entire healthcare industry, some secondary implications from the adjacent verticals are yet to fully cascade throughout the value chain. Just judging from the level of involvement of and extensive guidance from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) in interpreting various Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) provisions, it is quite clear that it will take some time for the industry to adapt to the newly imposed rules of the game. All in all, the healthcare ecosystem is not yet fully balanced, and in a time of ambiguity, it is difficult to make aggressive acquisition bets.

However, the above represents just short-term implications of healthcare reform. Its long-term consequences are quite the opposite. The PPACA made an already regulated industry even more regulated. With so many operating constraints and requirements, it is inevitable that small players that are teetering on the edge of solvency will either get out of the business or be acquired by the bigger firms. Moreover, our government recently introduced another strong incentive for operating on a mega-large scale, when being “too big to fail” serves as indemnification for taking a little extra risk under expectations of getting bailed out if something goes wrong.

All this makes me believe the consolidation trend will reaccelerate, and that within the next couple of years, we will see a number of intriguing M&A announcements. However, the potential M&A activity may not stay limited to horizontal consolidation with mergers of like companies, but also to vertical integration. In this respect, Kaiser’s model (payer/provider) seems to be quite a controversial example for replication because of the multiple pros and cons associated with such a business paradigm. But I’ll save that subject for a separate blog.