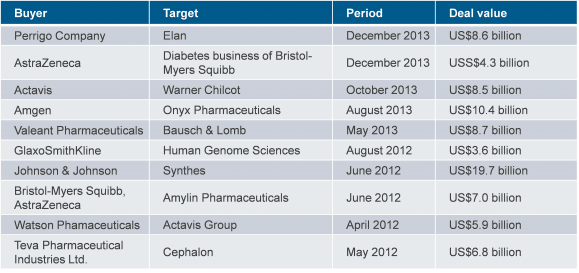

Novartis on April 22, 2014, announced a succession of deals in a sweeping restructuring. It agreed to buy GlaxoSmithKline’s (GSK) oncology products unit for US$14.5 billion, plus another US$1.5 billion subject to certain milestones. In turn, it divested its vaccines business to GSK for US$7.1 billion, plus royalties. The two companies also announced the creation of a new consumer healthcare business through a joint venture, in effect combining Novartis’ OTC drug business with GSK’s consumer business, with nearly US$10 billion in annual sales. In a separate deal, it hived off its animal health business to Eli Lilly for US$5.4 billion.

The deals – given their scale and impact – principally reshape Novartis, which has been evaluating its businesses since last year. The move reflects a strategic imperative to focus on higher margin products, such as cancer drugs, and let go of low margin ones, which rely on scale and volume. This signals a momentous shift for the firm, which under its previous chief executive transformed into an expansive healthcare behemoth, fueled primarily by M&As. The deals have substantial implications for GSK as well, reorienting its business across respiratory, HIV, vaccines, and consumer health products – together accounting for nearly roughly 70 percent of its sales. It also consolidates its position as the leading global vaccine player.

These changes reflect an important inflection point for the pharmaceutical industry. The industry is coming to terms with multi-faceted challenges arising out of patent cliff implications, middling R&D productivity, and rising consolidation, leading to a rethink of business models.

Life sciences M&A bandwagon

Bigger is not always better

Consolidation has been a standard practice adopted by Big Pharma to tide over industry challenges, maintain growth momentum, diversify into emerging geographical and product markets, beef up R&D efforts, and boost sagging drug pipelines.

However, with middling R&D productivity, patent cliff losses, and expansion into newer product/service lines, pharma companies are reconsidering the conventional paradigm to factor in these multi-pronged challenges. Incessant consolidation has had a detrimental impact on many companies with decreasing post-merger productivity, culture mismatch, integration challenges, and declining agility.

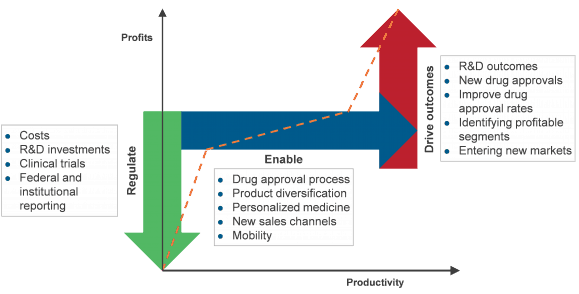

That has resulted in firms such as Novartis refocusing their priorities to focus on core competencies instead of having its fingers in too many pies. These restructuring efforts call for a carefully thought-out technology strategy that encompasses organization-specific challenges and hurdles. The roadmap for pharmaceutical firms must be evaluated on a profitability-productivity matrix to test for efficacy. The imperatives brought by wholesale value chain digitization in the pharmaceutical industry entail a re-examination of the organizational structure and resource allocation/rationalization required for driving top line and bottom line growth. Technology will serve as a key enabler to free up resources and ensure optimal utilization levels.

The profitability-productivity matrix of pharmaceutical firms

Big Pharma will continue to take the acquisitions route as new drug development becomes more expensive and exhibits declining productivity. But companies need to take a more balanced and individualized approach as they assess their unique value proposition and go-to-market strategies in order to thrive in the new world order.